Happy New Year and welcome, at last, to The Hachi.

I’ll be trying a lot of different things, but in the short term will mostly be focused on presenting my particular brand of Japanese sports bullshit in a more cohesive package.

While this is probably going to veer heavily toward the sports that are foremost on my radar (soccer chief among them), my goal is to highlight a bit of everything — wonderful, weird, woeful and everything in-between — and maybe turn my readers onto aspects of Japanese sports they may not have previously been aware of, even if it’s stuff I’m just learning about too.

Why The Hachi? As the Japanese word for ‘eight’ (八1), it’s mostly a too-clever-by-half reference to ESPN8: The Ocho — a throwaway movie joke turned into a genuine celebration of the unconventional and undercovered, which is the energy I want to bring to a segment of the sports world that I’ve never quite felt has had its time in the sun.2

I have no intention of turning on any sort of paywall for the time being. In return, it would be great if you could share this with friends, enemies, and anyone else who might be interested in learning more about the Japanese sports world.

So without further ado in this extra-large Issue #1 (I promise they won’t all be this long), complete with five variant foil covers, here are eight things to watch in 2024 that I think you might find interesting:

1. Dodgertown, Japan

What’s better than paying $700 million to secure the services of Shohei Ohtani, one of the best baseball players of all time, for the next decade? Paying another $325 million for his Samurai Japan teammate and arguably the most popular player in NPB last season, Yoshinobu Yamamoto, to wear Dodger Blue for 12 whole years.

I am, despite a childhood under the roof at Veterans Stadium watching Phillies games on Sundays, a passive baseball fan at best these days, bt you don’t really need to be more than that to watch either player do their thing and recognize that you are in the presence of greatness. So I’m less interested in talking about their talents on the mound (and the batter’s box, in Shohei’s case) and more intrigued at what their impact in LA will be.

To put it succinctly, money printer go brrrrrr.

In a pair of press releases, MLB’s merch manufacturer/retailer Fanatics said Ohtani’s No. 17 jersey not only smashed the previous record for the first 48 hours of sales — held by Lionel Messi upon his arrival at Inter Miami — but outsold MLB Japan’s total over the previous two years.

Meanwhile, Japanese travel agency HIS is already offering five-day tours for fans who want to take in a game at Dodger Stadium, guaranteeing second-level seats on the third-base line. Packages for the first month of the season run between ¥382,000 and ¥692,000 ($2,700~$4,900), depending on your choice of hotel and airline. Oh, and if you want your three-night hotel to yourself, that’ll cost extra. The other two days? Those are for transit.

There’s already reports of Dodger wine in Japanese shops — you can find bottles stateside for all 30 clubs, but it’s pretty impressive that importers were able to jump on this so quickly.

The Angels, despite wasting Ohtani’s greatness during his time in Anaheim, were at least smart enough to sell lots of ad space to Japanese companies. There’s no question the Dodgers, who already have a pedigree with Japanese players going back to Hideo Nomo’s groundbreaking 1995 arrival, are going to figure things out, and get millions of people across the Pacific wearing blue and white LA caps in the process.

2. This Samurai Blue generation may go the distance

It’s been roughly 13 months since head coach Hajime Moriyasu engineered a pair of World Cup rope-a-dopes that saw the Samurai Blue famously take down both Germany and Spain in the group stage — both vindicating those who have been saying that Japan’s player pool had always been talented enough to pull off such results, and frustrating the hell out of observers who don’t want to wait until the 60th or 70th minute for amazingly talented attackers like Kaoru Mitoma and Ritsu Doan to be let off the leash.

Now, the team is looking as good as it ever has — and will head into the 2023 Asian Cup (hosted by Qatar in 2024 after China kept its pandemic lockdown going just a touch too long for the Asian Football Confederation’s liking) as a strong favorite to win its fifth continental title.

After a draw to Uruguay and a loss to Colombia back in March that served as opportunities to call up a bunch of Paris 2024 hopefuls, the Samurai Blue romped to wins in their next nine games, including a 4-1 friendly dismantling of Germany and 5-0 victories against Myanmar and Syria in 2026 World Cup/2027 Asian Cup joint qualifying.

Those two WCQs featured a total of five goals by Feyenoord’s Ayase Ueda, while Reims’ Keito Nakamura has netted five in his last five appearances. They’re among dozens of Japanese players who are plying their trade for some of Europe’s prominent clubs, a list that includes Wataru Endo (Liverpool), Takehiro Tomiyasu (Arsenal), Takefusa Kubo (Real Sociedad), Mitoma (Brighton & Hove Albion), Daichi Kamada (Lazio) and of course the Celtic trio of Kyogo Furuhashi, Daizen Maeda and Reo Hatate.

Only three of Japan’s 36 goals in 2023 came from J.Leaguers, and two of the goalscorers — Atsuki Ito and Mao Hosoya — are reportedly already getting looks from UEFA scouts.

With only the Asian Cup and World Cup qualifiers awaiting Japan in 2024 — and with qualification for 2026 seemingly all but impossible thanks to the (*sigh*) expanded 48-team bracket — a strong performance over the next 12 months could become a statement of intent addressed to the rest of the world.

Not that those of us who have followed the team for years didn’t already know what’s up, of course.

3. Does Japan still have Olympic fever?

It’s fair to say everyone involved with the 2020 Tokyo Games left feeling a little burned.

If you don’t remember why, try sitting through all four hours of the opening ceremony — which played out in an empty National Stadium, itself a monument to compromise and the pitfalls of government-subsidized sports venues — while reminding yourself that this wasn’t a surrealist art performance, this was the opening ceremony of the Goddamned Summer Olympics.

We’ll never know how good Tokyo 2020 would have been without the pandemic. Heading into the new year I was certainly bullish, especially after the amazing six weeks that were the 2019 Rugby World Cup, which saw hundreds of thousands of visitors stream into Japan and pack stadiums across the country.

Instead, we got the Olympic Bubble (or close enough), sex beds (arguably the best thing I wrote during the Olympics), some genuinely heartfelt sporting moments, and a $13 billion bill at the end.

Just seven months later, Beijing had its turn, producing a Winter Games that might as well have taken place within the confines of a Disney backlot. Having experienced it firsthand and not wanting to digress too far, I will only say that it was weird as hell — but the main point is that two Olympics within a year was rough on everyone, especially the broadcasters and media who were increasingly left strapped for cash.

The ever-rising costs of covering major international sporting events — broadcast fees, the pandemic’s impact on travel, the Russia-Ukraine war’s impact on travel, the weak yen, you name it — has made it harder and harder to bring these events to the public, especially as viewers shift away from their TVs and toward second screens.

The 2022 FIFA World Cup was only aired in part on Japanese TV, with streaming service AbemaTV providing it for free online in a first for the country. The 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup nearly didn’t have a broadcaster until NHK stepped in at the last minute to take Nadeshiko Japan’s games as well as the opener and final, with the rest of the tournament available through the FIFA+ streaming service (though only in Japanese after the JFA interfered, which is a rant for another time).

Meanwhile, the short-term legacy of Tokyo 2020 is a bribery scandal that has soured public opinion and killed off Sapporo’s desire to host the Winter Olympics in the next 16 years.

Naturally, Japan will get behind its athletes once Paris rolls around in July. But it’s hard to believe that as many sponsors will step up to the plate, and even harder to imagine that the Japan Consortium — the alliance of public and private TV broadcasters who typically split Olympic duties every two years — will be ready to spend big to cover a Summer Games in such an inconvenient time zone.

4. Yuto Horigome is that man

For an intermission, take some time to watch one of the best street skaters in the world do his thing across Tokyo.

As an industry friend told me recently, Horigome doesn’t need to worry about how he does in competition, because he can easily leave the arena, shoot videos like this and rake in cash from Nike and his other sponsors.

That’s not to say he can’t come correct, however. After winning at Uprising and Street League in front of a home crowd, Horigome finished third at the recent Street World Championship 2023 in Tokyo, behind fellow countrymen Sora Shirai and Kairi Netsuke. The result moved Yuto up to seventh in the Olympic rankings after a slow start in qualifying, but it’s hard to imagine he won’t qualify for Paris and a chance to defend his men’s street gold medal.

More success by Japanese athletes in Paris should rekindle conversations that began after Tokyo 2020 — where they took three of four possible gold medals — on giving Japan’s growing skateboarding population more parks and opportunities to develop, with street skating remaining heavily discouraged or even illegal in most populated areas.

5. The top-light banzuke

To say that sumo is back is perhaps disingenuous — it’s been over a decade since the fallout of a bout-fixing scandal saw attendances plummet, and small crowds in 2020-2022 were caused by the same pandemic that impacted every other sport.

These days, however, the fans are back, the cheers are back, and the zabuton are definitely back, as we saw in July when Tobizaru took out yokozuna Terunofuji:

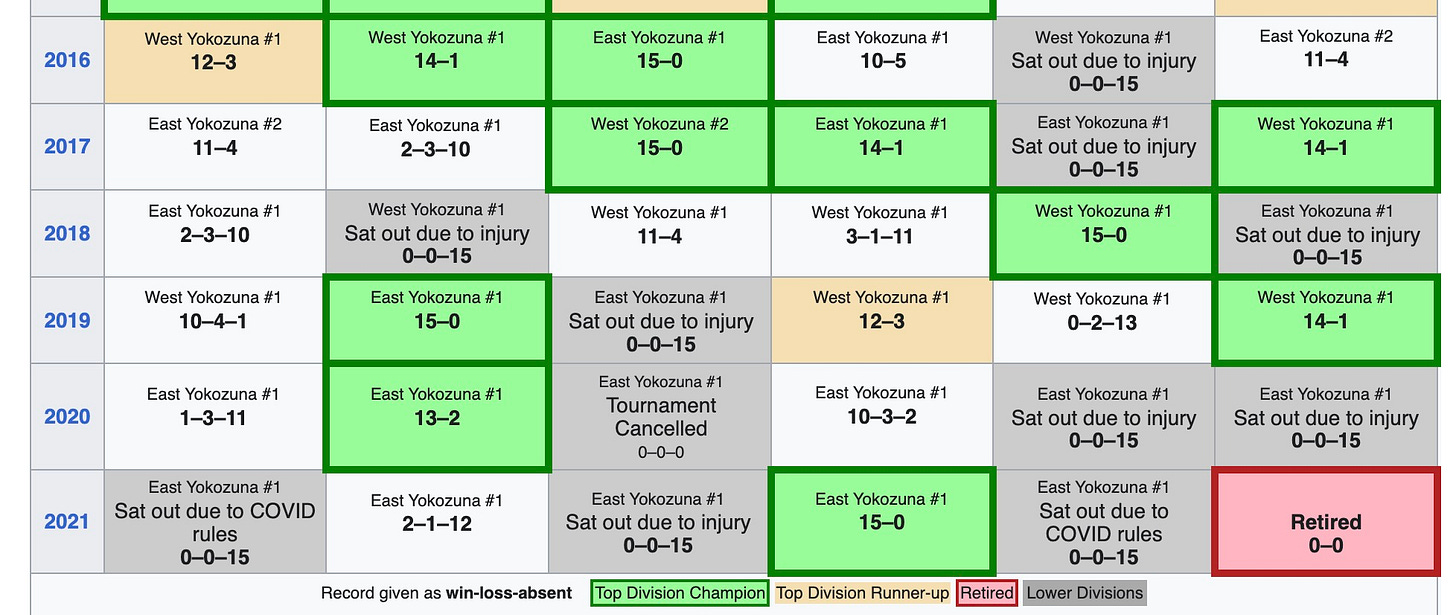

The problem is that we haven’t seen enough of Terunofuji, who overcame demotion to sumo’s second-lowest rank to rise all the way to the top rank. His often-injured knees, which require kilometers of athletic tape to hold together, have only allowed him to complete six of 14 basho since he was promoted to yokozuna.

He sat out four of six tournaments in 2023 due to injuries, and his record is starting to look like the latter stages of Hakuho’s — though the man now known as Miyagino stablemaster was still capable of a flawless basho when he was healthy enough to compete.

The problem sumo faces is that it’s not a terrific look to not have a yokozuna on the books. That’s not even from a practical perspective — the last couple years of tournaments have been wildly unpredictable and fun to watch — but more in the sense that the Intrinsic Spirit of Sumo practically demands a yokozuna’s presence.

A yokozuna is supposed to be dominant. They are supposed to be the last boss. Terunofuji’s lone 2023 title, a 14-1 run at the May Basho, is a sign of what upstarts must overcome if they want to achieve greatness. Without him, we got a 13-2 champion, three 12-3 champions, and even a 11-4 champion.

Unthinkable.

Each of the three ozeki — sumo’s second-highest rank — won at least one basho in 2023. None, however, were able to string together two straight titles as an ozeki3, the main requirement for yokozuna promotion.

Takakeisho has been particularly frustrating. His New Year Basho title was followed by an injury in Osaka, while his Autumn Basho victory (the 11-4) gave way to an unimpressive 9-6 finish in Fukuoka.

Kirishima, the winner at that Kyushu Basho, could reach yokozuna with a win at this month’s New Year Basho. He’d be the sixth Mongolian of the last seven to claim the white rope, causing extra consternation among old-school fans who would have loved to see Takakeisho become the first Japanese yokozuna since Kisenosato retired in 20194.

6. A year toward reforms

Last year saw both the J.League and B.League set down markers for ambitious 2026 reforms that could to change the face of professional sports in Japan.

The B.League’s reorganization — announced in July — seeks to significantly raise basketball’s standing in Japan as both a competitive sport and an entertainment destination. The current B1, B2 and B3 divisions will become the B.League Premier, B.League One and B.League Next, with the top flight tasked with becoming a world-class league and the next two divisions given the goal of broadening basketball’s national recognition and popularity.

With two Japanese players in the NBA, more coming up the NCAA ranks and the national team showing steady improvement in qualifying for the Paris Olympics, this is an ambitious reformation — especially as it will require clubs to put up big numbers both in the stands and on their balance sheets if they want to qualify for Premier entry — but one that seems feasible, given the league’s growth since its 2016 launch.

Meanwhile, the J.League’s board approved plans to shift its season calendar from spring-fall — starting and ending within the same calendar year — to fall-spring, matching European and South American leagues but requiring a seismic shift across all levels of the Japanese game.

This decision, forced in part by a similar calendar move by the Asian Champions League as well as the ever-growing effects of climate change, will in theory leave the J.League better prepared to profit more from the global transfer market, bringing clubs the revenue they need to develop the next generation of talent as players head to Europe in droves. The league also hopes it will lead to a safer environment for players, who won’t have to play nearly as many games in Japan’s sweltering midsummer heat and humidity.

But the move also carries the risk of leaving the J.League’s northern clubs out in the cold — quite literally — as they will need to figure out how to train and play in the winter months. It will also deprive many clubs of midsummer promotions that were big draws for crowds — goodbye, yukata-and-fireworks nights, hello, dreary mid-December afternoons.

With 2026 as the turning point for both leagues, the next couple seasons will be business as usual. The question is how much growth both can accomplish in the meantime, and how smooth the transition will end up being.

7. A united front for pro wrestling

One drum I will continue to beat — even after everyone has long moved on — is that Japanese sports never got the recognition it deserved for safely bringing fans back so early into the coronavirus pandemic, with NPB and the J.League allowing up to 5,000 per game as early as July 2020.

Besides the obvious cultural differences — it’s amazing what you can accomplish when your fans agree to go along with rules that protect the collective good rather than be assholes about masking — it required a herculean degree of coordination between the various sports leagues, both with each other and with the government. This was best embodied by the NPB-J.League Joint COVID Task Force, a revelatory show of cooperation between two sports that have long been considered rivals.

(This presser took place on March 12, 2020 — two weeks after the J.League suspended its season and just under a month before the first state of emergency was declared in Tokyo, and in retrospect it’s wild that a presser like that was taking place in person without masks, but time dilation is weird like that)

These government pipelines opened the way for clubs to smoothly coordinate with local health officials and receive whatever support was available from relief programs, staving off some clubs from potential economic ruin.

Professional wrestling was not as fortunate. Many of the country’s promotions suffered significant financial damage due to the pandemic, their returns to action further hamstrung by a reliance on indoor venues and a lack of access to timely information or avenues for support.

The formation of United Japan Pro-Wrestling is in many ways a reflection of where the industry sees itself, with nine founding promotions seemingly aware that they can either stand together or fall apart. They include the big guns — NJPW, NOAH and DDT — as well as two women’s circuits in Stardom and Tokyo Joshi Puro.

Per the Dec. 15 announcement, the UJPW will represent the industry as a whole, allowing members to share information while still competing in the marketplace. Among issues the new organization hopes to tackle are the creation of pipelines from other sports, the health and safety of wrestlers (especially as online fandom, like everywhere else, gets nastier) and big data analysis of each promotion’s customers.

My period of wrestling fandom ran from the mid-90s (Bret Hart, Shawn Michaels, early Undertaker) through the first few years of the WWE Attitude era (Stone Cold, The Rock, DX) when I went off to college, and I don’t have the time or headspace to get back onto that bandwagon again, but through my friends’ rekindled interest — as well as fantastic longform essayists like Super Eyepatch Wolf — I’ve gained an appreciation-by-osmosis of how the industry is evolving in what I consider to be the post-kayfabe era of internet fandom and metatextual analysis.

In that sense, it will be interesting to see what UJPW can accomplish not only in terms of improved municipal relations, but by applying some of the big-data work that pro sports leagues have successfully used to raise attendances in recent years.

8. Home sweet homes

With the attentions of fans (and potential fans) more divided than ever, Japanese sports are rapidly starting to shift past the old notion of venues simply being the packaging that contains games themselves, and into an era in which venues are an intrinsic part of the gameday experience, along with all the trappings you’d expect from some of the top stadiums and arenas in the U.S. and Europe.

Soccer and basketball teams in particular have benefited in recent years, with an increasing number of J.League clubs moving from tracked athletic grounds to boutique soccer-specific stadiums, as well as B.League teams establishing permanent arenas rather than hopping between multiple gymnasiums over the course of the season.

Notable openings of the pandemic era included Sanga Stadium in Kyoto, Okinawa Arena in Naha (which cohosted the 2023 FIBA Basketball World Cup) and Es Con Field near Sapporo, which will surely welcome an MLB opening series sooner rather than later.

These new venues have everything that older Japanese stadiums have lacked on the hospitality front: Giant super-high-definition screens, a greater variety of dining options, VIP areas and plenty of new spaces to allow sponsors to get their messages out.

This year will be an even bigger treat for stadium junkies. January will see the opening of the 5,000-seat Yokohama Buntai, set to become a new home for the Yokohama B-Corsairs as well as host wrestling events and concerts.

Meanwhile, February and March will mark the arrival of Kanazawa GoGo Curry Stadium, the 10,000-seat home of the J3’s Zweigen Kanazawa, and Edion Peace Wing Hiroshima, a spectacular-looking ground for three-time J1 champions Sanfrecce Hiroshima and their WE League counterparts, Sanfrecce Hiroshima Regina.

The B.League’s Chiba Jets Funabashi will get a new 10,000-seat home, LaLa Arena Tokyo Bay, from the spring, while September should mark the completion of Nagasaki Stadium City, featuring a 6,000-seat arena for the B.League’s Nagasaki Velca and a 20,000-seat stadium for the J2’s V-Varen Nagasaki.

Even more are coming down the pipeline this decade, with the Aichi International Arena expected to open in 2025, a new arena and a massively renovated Todoroki Stadium in Kawasaki set for 2028 and 2029, respectively, and new homes for baseball’s Tokyo Yakult Swallows (if they figure out the tree thing) and Yomiuri Giants also in the works.

These new venues shouldn’t struggle to fill seats, with inbound visitors already matching Japan’s record-high 2019 numbers, a feat that took less than a year after the borders reopened to tourism.

Hachi is also a homonym for 蜂 (bee/wasp/hornet), hence all the bee-related branding. I may decide in a while that it’s dumb — a determination you may already have reached — but I’m committing to the bit until I think of something better.

As opposed to Japanese pop culture as a whole, which still reigns supreme.

Kirishima’s first of two titles came at the Osaka Basho in March, when he won as sekiwake Kiribayama.

Kisenosato’s promotion after his 2017 New Year Basho title followed four runner-up finishes in 2016; after winning the Osaka Basho in his yokozuna debut he struggled mightily with injuries and only completed one more basho before his January 2019 retirement.

I liked the bee logo...