The Hachi #12: Things lost in the canal

What a destroyed statue means for Japan's sporting legacy

Hello, wherever you are! As you might have seen on Twitter or LinkedIn, I’m taking a pretty big career leap and re-entering the freelance world after five-plus years at the Japan Times.

While I am officially a free agent and open to inquiries (my email contact is here), I do want to emphasize that this newsletter will remain free for the time being, and I don’t plan on implementing a paywall until I’m confident that I can deliver an appropriate volume and quality of work to justify such a switch.

In the meantime I would very much appreciate it if you could share The Hachi with your friends and introduce them to my writing.

And now, something a little different from past issues.

The last couple of years have seen a battle continue to rage over the controversial redevelopment of Jingu Stadium, home of NPB’s Tokyo Yakult Swallows and one of just four stadiums still standing that can claim to have hosted Babe Ruth.

Opponents to the project have largely focused their attacks on two fronts: some are fighting to preserve a 98-year-old ground with a history as rich as Fenway Park or Wrigley Field, while others object to the developer’s plan to fell nearly 750 trees, among them a number of gingko trees that the Jingu Gaien area is well known for.

But as organizers distributed petitions and held press conferences, late March brought sudden word of the destruction of one of Japanese baseball’s treasured historical monuments.

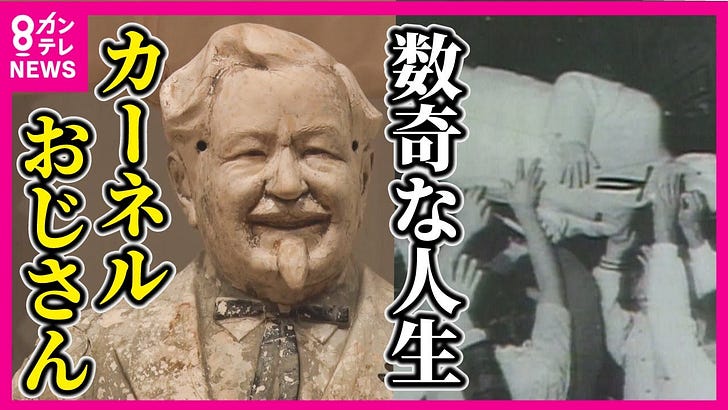

I am, of course, talking about the statue of KFC mascot Colonel Sanders that is believed to have haunted the Hanshin Tigers for nearly four decades.

Shohei Ohtani may be NPB’s most famous overseas export, but the Curse of the Colonel is arguably its most celebrated piece of lore.

Check YouTube and you’ll find news reports from 1992 and countless takes on the story, which is also a perennial Reddit favorite.

Odds are you’ve heard the tale in some form or another: On Oct. 16, 1985, Tigers fans celebrating their first Central League title in 21 years commandeered a Colonel Sanders statue from a KFC branch in Osaka’s Dotonbori nightlife district, having convinced themselves that it bore more than a passing resemblance to Hanshin slugger (not to mention future Oklahoma state senator and Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame inductee) Randy Bass.

After giving the statue a few do-ages, fans decided that the Colonel should also partake in another one of their activities: a dive into Dotonbori’s famous canal. But while fans who leapt into the filthy water usually made it back out, the same could not be said of the statue.

The Tigers went on to win the Japan Series weeks later, with Bass taking MVP honors. But as the statue evaded the city’s annual river cleanups, Hanshin experienced a swift downturn in fortune, finishing at or near the bottom of the Central League table in nearly every season between 1986 and 2002.

The death of a fan following 2003’s Central League title celebrations — during which thousands jumped into the canal — spurred the reconstruction of Ebisubashi Bridge in order to deter further copycats. The Tigers went on lose that year’s Japan Series to the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks, and the curse lived on.

The statue was at last recovered —in parts — by divers in March 2009, its coloring faded and its left hand and trademark glasses missing. After undergoing restorative work, it went on display near Koshien Stadium, and was eventually sent to KFC’s Japanese headquarters in Yokohama before being returned to the company’s Kansai office in 2017.

There it sat in a display case, out of the public eye but still smelling of sludge as paint peeled from its legs, according to Asahi Shimbun reporters who visited the statue in September as the Tigers were romping to the Central League pennant.

Two months later and they were Japan Series champions. The curse, it seemed, was lifted — but the statue was too fragile to make an appearance in the Tigers’ victory parade, as many had hoped for.

On March 19, KFC Holdings Japan revealed the statue’s fate: rather than let it deteriorate further, the company held a memorial service known as ningyo kuyo (人形供養), a rite for the disposal of dolls and stuffed animals. Company president Takayuki Hanji offered the Colonel one last order of sake and fried chicken, as seen in this rather surreal footage, which has lived rent-free in my head for the last couple of weeks:

Logically, it’s hard to argue with KFC Japan’s decision: The Tigers are again NPB champions and the Colonel is no longer a symbol of a curse, but rather a smiling beacon of patience and perseverance. It’s also clear that 24 years of submersion did not treat the statue kindly, and that there was only so much that a fried chicken company could be expected to do in terms of preservation efforts.

But on an emotional level, it’s a gut punch. Much in the same way that sports nerds of many stripes keep our ticket stubs, programs and team sheets — whether it’s a championship game or a midseason snoozer — because of the historic value we imbue in them, I am overwhelmed with the sense that the statue belonged in a museum, and I wonder if more couldn’t have been done to preserve it, either in physical or digital form.

I rue that fans weren’t able to say goodbye, and that the Tigers, the Central League, NPB or even the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame weren’t in a position to take a more active role in preserving an artifact recognized by baseball fans around the world. If Cooperstown can house a 135-year-old baseball in its collection, surely something could have been done for the Colonel.

But what honestly troubles me the most is this: If this icon of Japanese baseball could be destroyed at the whim of its owner, what other sports-related artifacts and cultural assets are we at risk of losing?

It’s a question the Japanese sports world will find itself having to answer with increasing frequency as the pioneers of the industry age, organizations slim down and prized possessions are left in limbo.

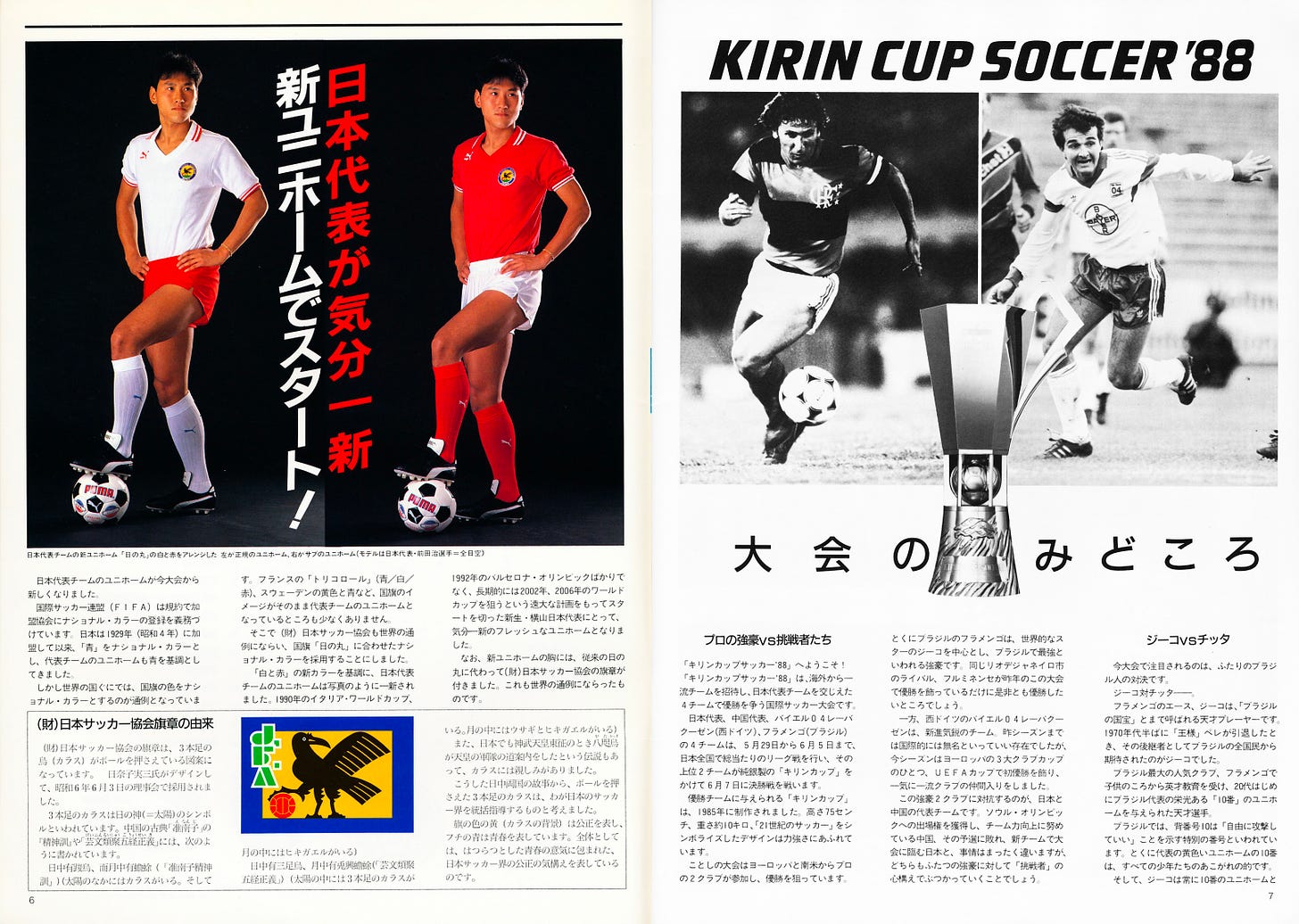

When the Japan Football Association relocated its headquarters from JFA House in 2023, the Kobe Kagawa Soccer Library — headed by Hiroshi Kagawa, at 99 the world’s oldest active soccer writer — hoped to inherit books and pamphlets that were at risk of being destroyed, even as Kagawa expressed concern over the resources needed to process and store the materials.

Meanwhile, the Japanese Football Museum remains in boxes — as does the Japanese Football Hall of Fame — having been marginally replaced by Blue-ing, a tech-heavy digital experience and cafe housed within Tokyo Dome City.

Most significant print material on Japanese sports has never been digitized, while the frailty of the Japanese internet — especially sites from the pre-smartphone age — means that so much content has been or could potentially be lost forever.

The amount of that content that’s been translated into English or other languages might as well be a drop in the ocean. And that’s to say nothing of the other precious artifacts — game balls, worn uniforms1, mascot merch and all the rest — that are in storage limbo, or in an area vulnerable to natural disasters, or set to be inherited by relatives with little emotional attachment.

There are no easy answers to this problem. The status of the Prince Chichibu Memorial Sport Museum and Library remains in limbo a decade after its closure, while some of the country’s other sports-related museums such as the Japan Olympic Museum and Sumo Museum are woefully undersized. Archiving — or at least digitizing — all of the books, magazines, pamphlets and programs that are out there would require a monumental amount of resources.

But the Japanese sports world surely deserves more than to have some of its best and most interesting stories survive only as a handful of YouTube videos, dead Yahoo News links and Reddit TIL threads.

When we lose the big things so easily, it shows how little it would take to lose the smaller things as well. It scares me, as someone whose mission it is to contextualize Japanese sports to international audiences, and it should scare everyone else with similar aspirations.

More must be done, or the Colonel’s demise will only be the beginning.

My white whale is finding one of the 18 fans with a Sanfrecce Hiroshima uniform from the 1995 game in which they famously had to borrow replica shirts from fans after their equipment manager didn’t bring home kits

Bring back the Japanese Football Museum, I say! Or at least the efforts to digitize and preserve printed materials could be undertaken by intrepid and careful librarians and archivists. What an interesting opportunity.